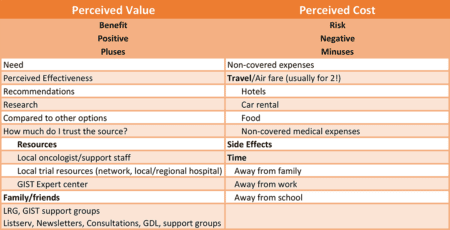

At the most basic level, cancer patients join clinical trials because of perceived value and perceived cost. In this context, perceived cost refers to more than just financial cost, although that is important. Perceived cost includes not only financial costs, but also includes other things such as perceived side effects, any cost in time, which may include time away from family, time away from a job, etc.

At the most basic level, cancer patients join clinical trials because of perceived value and perceived cost. In this context, perceived cost refers to more than just financial cost, although that is important. Perceived cost includes not only financial costs, but also includes other things such as perceived side effects, any cost in time, which may include time away from family, time away from a job, etc.

The word perceived deserves special emphasis. The patient will ultimately place a value on their various options as well as a cost based on what they know or think they know.

Perceived Value

How does a patient determine value? The first part of such a determination is based on need. Patients doing well on approved therapies with a good prognosis have little need for a clinical trial, so there is little value to them. At the other extreme, patients that have failed all approved therapies have much greater need.

The second part of placing a value on a trial depends on awareness. In order to have a perception of the value of a trial, the trial must enter into the realm of the patient’s awareness. This awareness can come from a number of different sources.

- Their local oncologist, or their support staff

- The local oncologist might be affiliated with a network or a local or regional hospital that offers clinical trials

- An oncologist (or other doctor) at a GIST expert center (GIST referral center)

- A recommendation from other patients (e.g., LRG listserv)

- Consultation with a patient support/advocacy group

- Their own research

- Recommendations of family or friends

For patients that have both need and awareness of a trial, they must then start the process of assigning value and assessing the costs of the trial (even if they are unaware that they are doing so) and then comparing this trial with all of their other options, including other trials, off-label treatment (if available) and no treatment. The patient must place a value and a cost on all of those options as well. Placing a value and a cost on their options doesn’t necessarily mean an actual number, or a checklist, although some patients might be that organized. It can simply be a process of mentally coming to a decision based on the things they know.

Perceived effectiveness

Via Recommendation: Someone told you about effectiveness.

With need of a trial established and the patient becoming aware of the trial as on option, including meeting eligibility requirements (the process of verifying eligibility may come early, or it could come later), the patient will typically next look to perceived effectiveness of the drug or therapy. Some of the steps that have taken them to this point will already have started the process of assigning a perception of efficacy. For example, when a patient’s oncologist informs a patient about a trial, the oncologist will almost always give the patient their impressions of the trial, both good and bad. In fact, the patient will usually place some value on the trial just because the oncologist recommended it or even just informed them about it.

No matter what the source of awareness was, each of the other sources, perhaps more accurately, resources, might be consulted about the trial. The patient will then begin assessing a value based on the strength of the recommendation as well as their confidence in the resource. The following are examples illustrating the extremes that a patient might be exposed to:

- A local hospital clinical trial team informs the patient that there are no GIST specific trials, but they do have several trials for which the patient might be eligible. Since the recommendation is based solely on eligibility and not on any GIST-specific rational, this might result in a low valuation of potential efficacy by the patient.

- A patient hears about another (or more than one) patient that is enrolled in a trial. They often hear about this from other patients, such as on the LRG listserv. In fact, with hundreds of other patients with the same disease, this is probably the best place to learn about trials that other GIST patients are on. From an email community you find out not only that a trial exists, but often even how they are doing including (sometimes early) reports of efficacy, side effects, logistics, etc.

- A patient goes to a GIST expert center and is offered a GIST-specific clinical trial (or in some cases, even a choice between two or more trials). Since the recommendation is coming from a GIST expert, it might be assigned a higher value from the patient; especially if there is a positive report of early signs of efficacy or strong rational from the expert GIST doctor.

- A patient receives a recommendation from a well-meaning, but not very informed friend, that trials are for guinea pigs and that they should forget about them and try an alternative treatment that they read about on the internet.

- The previous example is not intended to cast an aspersion on friends or family. Very often they are your #1 resource. It is especially common for a spouse or significant other to assume the role of “chief researcher” in the family. But this role is also often filled by other family members as well and less often by friends.

Via Research: You did your own research into effectiveness.

Many patients may skip this step entirely, relying solely on recommendations from their resources. However, some patients will do significant research into drugs/trials they are thinking of joining. For these patients, the ability to read and process the often technical information they find is important. Their ability to understand and more importantly, to evaluate this information is often related to how long they have been a patient and how much they have already learned about this process in the past.

Resources that this group of patients might use include:

- LRG Clinical Trials Database

- gov database

- Other databases

- Meeting abstracts; ASCO is an especially important source of these

- Expanding your list of recommendation resources, such as consulting with the LRG Clinical Trials Coordinator to learn about options, or calling the LRG office, following leads by contacting and actually talking to the people conducting the trials or doing the research that led to the trial.

- Search engines may lead to articles from other sources, such as a newspaper article, such as a medical journal article, etc.

Perceived Cost

As we mentioned earlier, cost refers to more than just money: It’s really the total “cost” to the patient. Another way to think about it is, it’s everything negative about a trial; the negative side of a balance sheet.

Just like when looking at value, the word “perceived” is important. Perception may be different than reality, but perception is reality for the patient.

Financial cost is often a consideration when considering a trial. Few GIST trials are offered at so many centers that a patient is likely to find one locally. Travel, especially travel by air is often required to participate in a clinical trial. Luckily, most trials only require a patient to be seen at two to three month intervals. Often there are more visits required earlier in the trial, such as a return at one month, and expanding to three months or so between visits. A typical visit to a trial that requires air travel might incur costs similar to this:

- $700 – Air travel for a patient and caregiver (often a spouse or significant other)

- $300– Hotel cost for two nights stay (often only 1 night’s stay is required)

- $150 – Car rental or taxi fares

- $150 – Food

Luckily, most, if not all, medical costs are usually covered by insurance. There is typically no cost for the trial medications, as they are typically not yet approved for general use.

In addition to placing a value on possible benefit, patients will place a value (typically a negative value) on potential side effects. In some cases, such as an early phase I trial, side effects will be unknown. However, in most cases, patients can learn about previous reports of side effects from early trial reports, their doctor, or from patients already or previously enrolled in the trial.

Time is another potential cost to the patient. Time away from their jobs or their family. This can become more important if the patient thinks their time might be limited. However, with time it can also work the other way; if the patient believes that the trial might be very effective, they may think that it could buy them more time with family.

Cancer therapies have become more effective in recent years; in some cases, much more effective. With this shift patients, have come to expect more potential benefit from trials. The days of entering a clinical trial with only an altruistic motive of possibly helping someone in the future are fading. Patients, especially GIST patients, are starting to look to trials as a means of extending their therapeutic options. With this comes the need for resources to help them evaluate their options. Resources like doctor recommendations, patient experiences, help from family and/or friends and trial databases . . . and the tools to be able to evaluate their options.